With his innovative ideas, revolutionary thinking, and groundbreaking practice, Wharton Esherick (1887-1970) was instrumental to the evolution of American design. In fact, Esherick pioneered the concept of design-art during the 30s with his radical artisanal furniture, long before this term was coined to describe artistic process in creating functional objects. Yet, while widely recognized by scholars, collectors, and museum curators for his influential role as the Godfather of the American Studio Movement, Esherick is an obscure figure, and his exceptional accomplishments have remained an enigma.

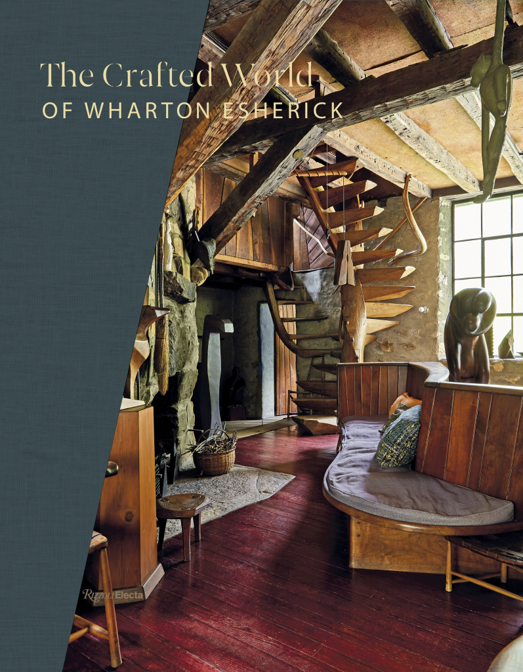

A new monograph, published with the traveling retrospective ‘The Crafted World of Wharton Esherick, (opened in October at the Brandywine Museum of Art), changes this and illuminates his significance. While reexamining how Esherick’s practice and discourse shaped the craft movement during the postwar decades with six scholarly essays, it is the first publication offering a comprehensive series of photographs of his former studio by Joshua McHugh, and other great images of his interiors and bespoke furniture. In the series Interior Design: Then and Now, I invited two guests to examine Wharton Esherick’s exceptional legacy: Emily Zilber, Director of Curatorial Affairs at the Wharton Esherick Museum (and the book’s editor), along with design historian Sarah Archer, whose contributing essay ‘The Radiant Curve: Pattern and Dimensions in the Work of Wharton Esherick’ traces the evolution of his vocabulary.

Esherick’s relationship with nature was central to his cutting-edged approach, and his visual language was rooted in nature, landscapes, and his world in the countryside. His ‘desire to recalibrate humanity’s relationship with nature,’ Zilber says, was inspired by William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement. Even as a student at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, nature greatly interested him. And while he had a great interest in urban places, he spent his life living and working in the Pennsylvania countryside, and believed that our surroundings should enhance our lives in multiple meaningful ways and found intimacy in nature.

His innovation was twofold: first, in brilliantly translating the art movements of his time—German Expressionism; Constructivism; Expressionism of Swiss architect-philosopher Rudolf Steiner – into three-dimensional, functional objects. He interpreted their key emblems – cubism, crystalline, glass (primarily expressed in architecture and stage design) into furniture. Furthermore, Esherick was the first to enter the studio to create modern design when the entire world was fascinated by the advent of the industry, and modern design was perceived as connected to industrial production. He taught a generation of artists that modern design could be handcrafted, that artistic visions can be married with craft and skills, and that craft is not contradictory to design. At the core of his oeuvre as a woodworker was understanding wood as an artist’s material and the quest to keep pushing the boundaries of his craft. ‘Esherick,’ Archer says, ‘had a special relationship with wood’ and in that, he influenced other artists and designers.

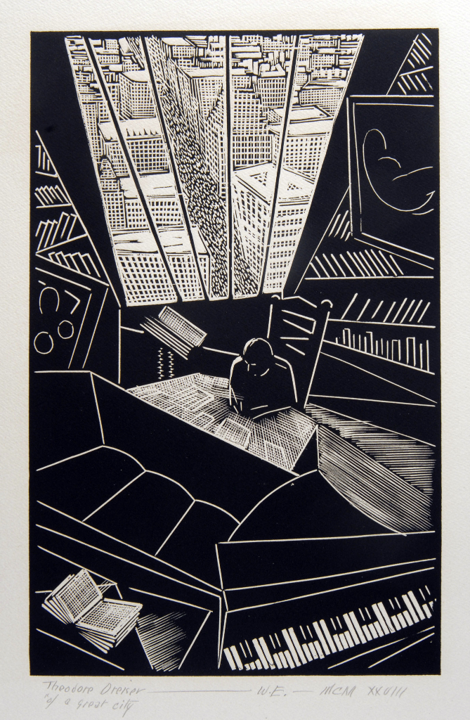

He married Letty Nofer in 1912 and settled in a farmhouse in Valley Forge Mountain, west of Philadelphia, where he painted Impressionist-style canvases. The turning point was a family visit to Alabama and a meeting with Marietta Pierce Johnson, an educational reformer and founder of a progressive school called the School of Organic Education. There, Esherick first experimented with wood, creating woodblocks and printmaking. Transitioning to furniture was seamless, and by the early 30s, he had achieved his own personal style.

The piece that most signifies that style is certainly the iconic free-standing spiral cubist staircase, crafted in 1930 for his studio. Still, it left the studio twice for exhibitions, and is the touchstone of his early vocabulary. Esherick perceived his home studio, which he built between 1926 and 1966, now the Wharton Esherick Museum as the ultimate representation of his vision, and famously called it “an autobiography in three dimensions.”

In 1935, he created the interior at the Philadelphia’s Main Line home of Curtis Bok, Justice of the Pennsylvania State Supreme Court. It was the ultimate expression of Esherick’s early ideas about forms, design, and woodworking. Bok was the perfect patron who allowed Esherick to forge the most ambitious interior program, including furniture, fireplaces, staircases. The oak-paneled music room, today in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, was particularly energetic, dramatic, and spectacular.

As Esherick established himself in design, receiving various commissions, arrived the turning point immediately after completing the Curtis Bok’s commission. He was invited to create an interior space at the Pennsylvania Hill House, a pavilion at the 1939-40 World’s Fair in New York, where he expressed his own language, while including his own staircase, brought to New York from his studio. While his interior was much more radical and intriguing than the others included in the same pavilion, Esherick began moving away from working with exotic woods and from his Expressionist period. From that time onwards, his practice became more successful and his language became more organic, unlike other American postwar furniture.

As much of Esherick’s furniture was bespoke, built-ins, it does not exist in large quantities as pieces by the second generation of the American Studio Movement such as George Nakashima, Paul Evans, and Wendell Castle who were produced much more. Therefore, he is hardly represented in the marketplace and absent from the international marketplace. For this reason, Esherick is not known to the broader public, but ‘The Crafted World of Wharton Esherick’ brings to light his innovation and extraordinary vision, demonstrating his influence and telling his story and the new life he brought to the medium of wood.

All images from the monograph, photography by Joshua McHugh.