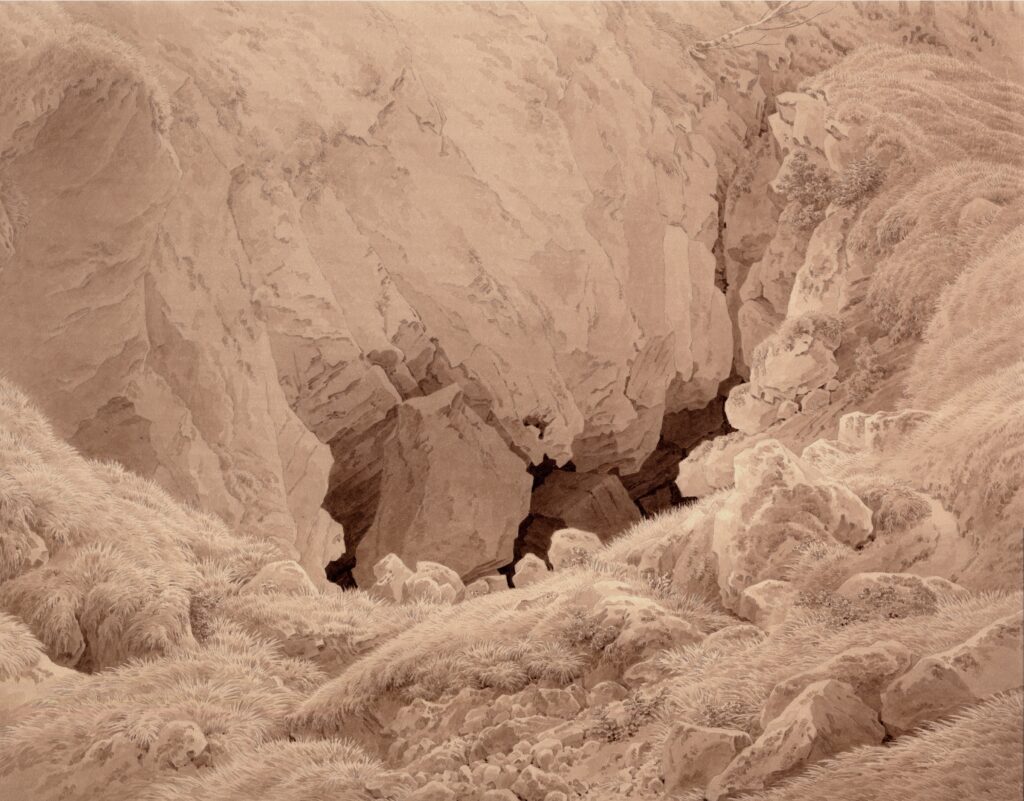

The Royal Danish Collection, Copenhagen (I, 3 a-3)

Photo credit: HM The King’s Reference Library, The Royal Danish Collection.

No artist has glorified nature as well as German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), whose exhibition, Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature, opened last week at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. To be honest, I could not wait for this first major retrospective of Friedrich in the US, marking what would have been his 250th birthday. Why? Because I was introduced to Friedrich’s paintings as a freshman in college in the introductory course to Modern Art, and it inspired me to become an art historian. The way in which he had passionately presented nature as a personal and philosophical discovery, and how he blended nature and the sublime, captured its spirituality as an expression of the inner soul. This left an impact on me, and has had a significant, lasting influence in my life.

I was also taken by the way historians interpret and write about Friedrich’s paintings, because their symbolism was rooted in his Christianity and in the Romantic ideal that perceived nature as the representation of God. His canvases and drawings present nature in the most beautiful way, but also as timeless and connected to the fundamental and universal problems and values of human existence. This was how I learned for the first time that interpretation of art can be as powerful as the art itself, and that the role of the curator is no less important than that of the artist. Yet, I have hardly seen Friedrich’s paintings and drawings in person, only in books. So, this is a dream exhibition for me: a once in a lifetime opportunity to see 75 works under one roof. No less than 30 lenders in Europe and North America made it possible to see work from every phase of his career, capturing the full essence of his legacy.

Friedrich was a member of the Romantic Movement, which sought to advocate for the importance of imagination and appreciation of nature as a way to turn away from the illness of the Industrial Revolution. Nature, to this generation, was heroic, mysterious, exotic, and sublime. As you walked through the galleries at the Met, you would be stunned by the breathtaking German landscapes—particularly by the expression of light. For four decades, Friedrich depicted the Baltic coast and the landscapes surrounding Dresden, the city where he made his career.

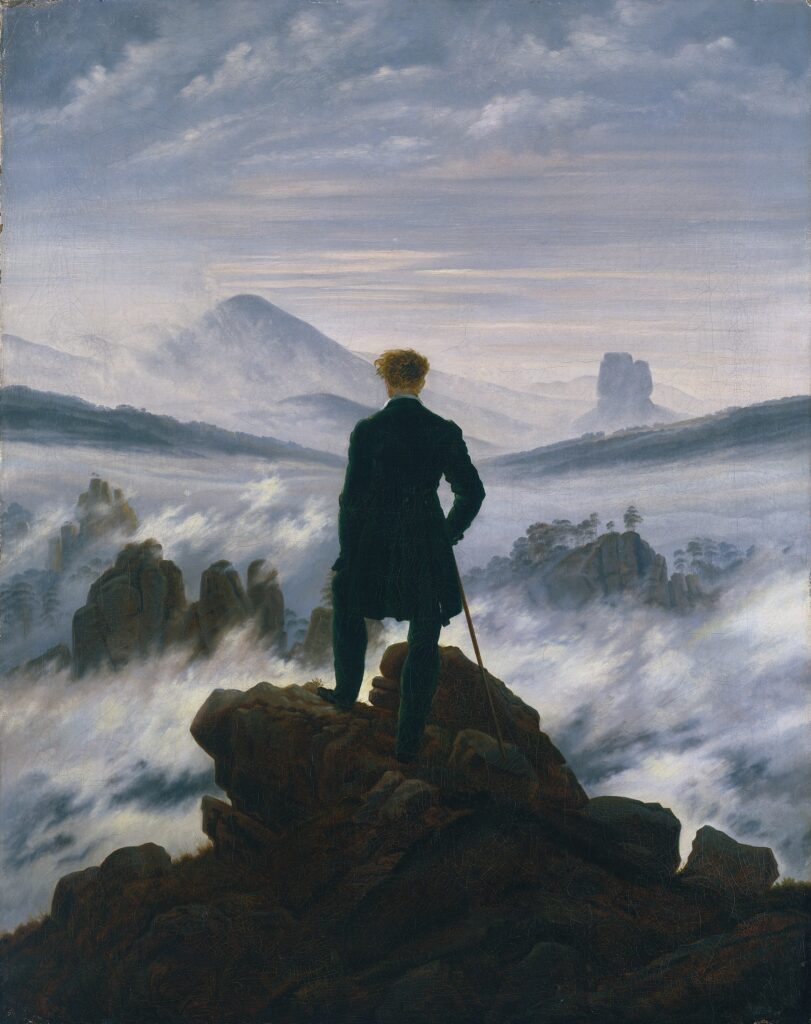

His works present nature not only as a source of beauty and consolation, but also as a reflection of the aspirations, sorrows, memories, and beliefs that define our personal and collective humanity. With their intensity and emotional focus, the two paintings which brought me to tears are the famed and influential Monk by the Sea, painted in Dresen, depicting a figure dressed in a long garment standing on a low dune sprinkled with grass along the horizon; and his amazing The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, which is a self-portrait presenting a metaphor for the unknown future, and it has never traveled to the US before. Nature has never looked more beautiful, nostalgic, or emotional than through the lens of Caspar David Friedrich.

The exhibition will be on view through May 11th, 2025.

Hamburger Kunsthalle, on permanent loan from the Stiftung Hamburger Kunstsammlungen, acquired 1970 (HK-5161) Photo by Elke Walford

Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig (G 1217); Photo credit: bpk

Bildagentur /Museum der Bildenden Künste, Leipzig / Bertram Kober/ Punctum Leipzig / Art Resource, NY

Freies Deutsches Hochstift, Frankfurter Goethe Museum, Frankfurt am Main (IV-1950-007)

Photo credit: © Freies Deutsches Hochstift / Frankfurter Goethe-Museum, photo: David Hall

Thank you for your essay – I’ve always enjoyed Friedrich and it’s wonderful to see him get such significant consideration. I’ve been listening to a podcast about it with two art historians from the Met – one quoted Friedrich in which he used the word “compassion” to talk about “Cross on the Mountain” – I noticed you had used it also. It’s not usually a word used to describe the sublime, yet certainly it’s there in Friedrich.