He was tall and handsome with red hair and blue eyes, which is unusual for Catalonian people of his generation. As a young man, he was a dandy who dressed fashionably and smoked cigars. Despite his good looks and charm, when he proposed to his friend’s niece she declined because he was “clumsy when it came to picking up a knife and fork.” After all, Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926) did not grow up in the big city and was not sophisticated enough for this urban girl. He never proposed again and lived as a single man, instead devoting his life to architecture.

A new biography of Gaudí by Michael Eaude brings to light the life and work of one of the most beloved architects in history. Eaude puts an emphasis on how he turned his love for the medieval, passion for the crafts, and strong patriotic nationalism into some of the most renowned and magical yet eccentric buildings that were built around the turn of the century and which draw millions of tourists to Barcelona today. This resulted in the Catalan architect turning into the city’s main tourist attraction, and in recent decades, three of his buildings were declared World Heritage Sites by UNESCO.

Gaudí was a contemporary man who—like almost any architect or designer of his generation—was inspired by John Ruskin, William Morris, and the Pre-Raphaelites, the heroes of that era. It was not only their call to return to the purity of the medieval past that he was drawn to, but also their passion for the creative process of the handmade while rejecting industrialization, all of which came to shape his extraordinary oeuvre and his experimental architecture. While Gaudí loved ornaments, he had never applied them to his buildings, yet always made them integral parts of his architecture, just as Morris preached. This brilliant aspect of his work brought him into the pantheon of modern architecture. His two major apartment houses—Casa Milà and Casa Batlló, which are both open to the public today—capture his ultimate and brilliant ability to create interiors which completely reflect the exteriors. However, unlike the British fathers of modern design who insisted on the medieval dream and on the traditional crafts, Gaudí was a rationalist who admired French architect and theorist Voillet-le-Duc and his call to study medieval buildings, but with the intention to improve them with modern techniques rather than copying them.

Gaudí knew very early in his life that he wanted to become an architect, and achieved enormous success by his mid-30s, just 10 years out of school. His clients included the Count Eusebi Güell, the wealthiest man in the country who sought to build the fanciest, biggest, and greatest buildings in Spain and to embed them with nationalistic symbolism. Güell shared his patriotic ambition with his architect, who perceived architecture as a way to construct the future of Catalonia. Gaudi also had ambitious religious orders.

At 31 years old, he got the job of his life when was commissioned with Sagrada Familia, which he initially thought would take 10 years to complete. The unfinished building had been abandoned for years until a new phase of construction started in 1952, and ever since then it has been a site of debate. In the 1960s, for example, architects and artists such as Le Corbusier and Joan Miró signed a letter against keeping the continuation and advocate for leaving it unfinished; George Orwell famously called it “one of the most hideous buildings in the world.” In 2014, it was anticipated that the building would be completed by 2026, the centenary of Gaudí’s death, but this schedule was threatened due to work slowdowns caused COVID-19 pandemic and an updated forecast reconfirmed a likely completion of the building in 2026, with the work on sculptures, decorative details and a controversial proposed stairway leading to what will eventually be the main entrance is expected to continue until 2034. 150 years later!

The book is an engaging and easy read for anyone interested in architecture and in Gaudí. I would recommend it for anyone traveling to Barcelona because it provides a survey of the architect’s work, but also places it in the context of the Art Nouveau movement both in general and more specifically the Catalan version of Art Nouveau, called Modernisme (a term Gaudí rejected). I found the concluding chapter which examines the legacy of Gaudí and the evolution of his rediscovery to be particularly helpful and fascinating. It is hard to believe that some of his most known buildings were neglected until his rebirth in the 1980s and 90s, for so long that their bright colorful frescoes and mosaics and frescoes were cacked and chipped.

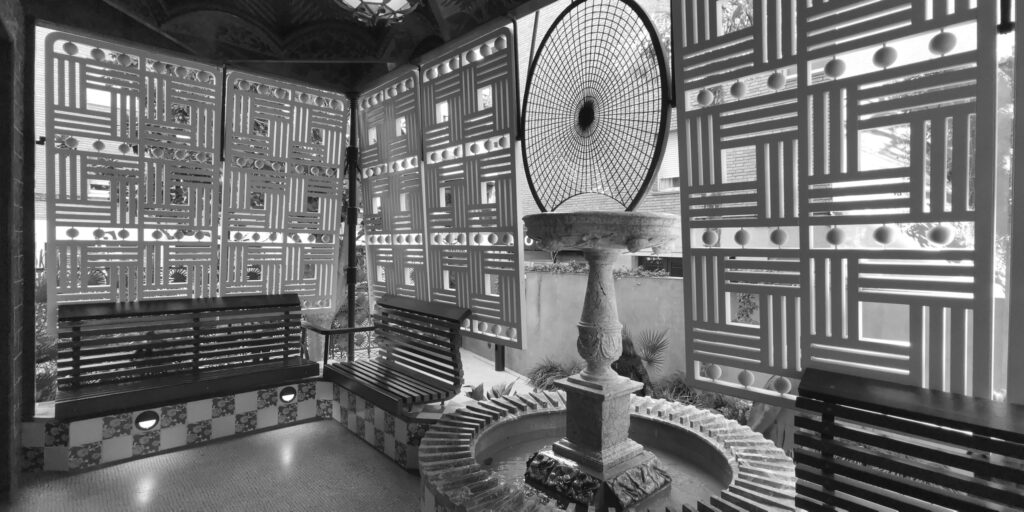

The fact that eccentricity was adopted in the 1930s by the Surrealists Man Ray and Salvador Dalí reveals that this group of artists were inspired by his eccentric architecture while the rest of the world went modernism. While British architecture historian Nikolaus Pevsner neglected to include Gaudí in his early bible of modern architecture, the fact that Gaudí was included in the 1933 MoMA groundbreaking exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism indicated this strong connection. I like the chronological order of the book, because the reader is able to follow the evolution of Gaudí’s vocabulary from Orientalism to Art Nouveau, from the Medieval to the Modern, from the heavy to the airy. However, the black-and-white photos do not do justice to Gaudí’s buildings, of which allure and sensuality are defined by their textures and colors. The lack of colored images tranishes the read, to my opinion.

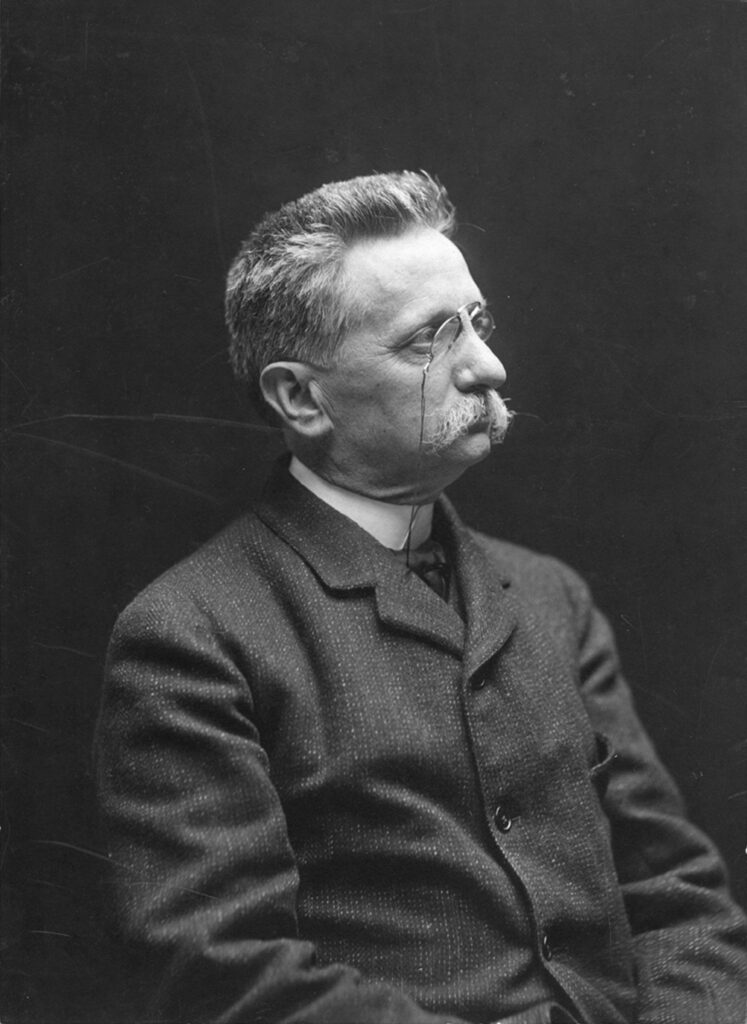

Through this book, we learn that Gaudí is a strange phenomenon in the history of architecture. His successful contemporaries, particularly Llouis Domenech I Montaner, have not received a fraction of the attention that Gaudí has and is still receiving from academics, curators, and pop media. It is unfortunate that the entirety of his archives were lost during the Spanish Revolution of 1936, as he had never published any books, and the only surviving account by him is just one newspaper article. What does remain is his buildings. Endless architects found inspiration in his work, such as Le Corbusier, Louis Sullivan, Walter Gropius, and Santiago Calatrava, but nobody really copied him. “Rather than style,” Eaude suggests, “this is a general, intangible influence.”

DANIELLA, HIS WORK WAS AN EARLY INFLUENCE ON MY WORK ONCE I LEFT THE SCHOOL FOR AMERICAN CRAFTSMAN. IT WAS WENDELL CASTLE WHOM FIRST INTRODUCED ME TO HIS WORK. I WILL SEND YOU AN IMAGE A PIECE THAT WAS INSPIRED BY GAUDIS WORK.

MANY THANKS,

DAVID EBNER

David, always great to hear from you and I cannot wait to see this exquisite table in person.