Asked to visualize the work of legendary Belgian architect Victor Horta, most design lovers readily call to mind a widely disseminated photograph of the staircase in the Hôtel Tassel, which Horta designed and built in Brussels between 1893 and 1896, at the dawn of the Art Nouveau era. This iconic image, reproduced countless times in design history accounts since the 1970s, captures the sinuous iron railing and whiplash wall and floor motifs moodily illuminated by the yellow-orange hues cast by the flower-shaped chandelier and sconce. In my recent Interior Design: Then and Now program, my guest Iwan Strauven, co-editor of the newly-published catalogue Horta and the Grammar of Art Nouveau, revealed that this enduring picture, which was shot at night, distorts Horta’s subtle color palette and obscures the extraordinary lightness of this architectural masterpiece.

Accompanying the 2023 exhibition of the same name at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Center for Fine Arts, in Brussels (BOZAR), the publication marked the 130th anniversary of Horta’s Hôtel Tassel and presents new photographs by architecture photographer Maxime Delvaux that showcase the famous townhouse in a completely different light—literally. The result is a far more accurate depiction than we’re accustomed to, demonstrating just how inviting, airy, and modern the space truly is. The curatorial team’s goal for both the exhibition and the catalogue was to correct the record and foreground Horta’s achievements as an decidedly modernist architect, who, under the influence of French architect and theorist Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, prioritized honesty in materials, rationalist construction methods, and open-plan design over the sensuous surface decoration with which he has been most closely associated. Delvaux’s use of a large-format analog camera and abundant natural light, in fact, beautifully portray Horta’s extraordinary structures as a powerful counterbalance to his distinct ornamentation.

The true look of the still-privately-owned Hôtel Tassel is not the only surprise you’ll find in the handsome volume. You’ll also discover that Horta’s decorative motifs, which we have long been told drew inspiration from nature, were in fact couched more deeply in artifice, ultimately inspired by Japanese calligraphy. Many of the most commonly accepted narratives about Horta, it turns out, have been overly simplistic. A figure of great complexity, he was both a traditionalist and the inventor of a paradigm-shifting visual language; he simultaneously embraced the handcraft revival initiated by the pan-European Arts and Crafts movement in the late 19th century and the latest construction technologies that would propel 20th-century architecture toward the future. Horta’s genius, Strauven suggested, was introducing greenhouse architecture to the domestic sphere, which greatly influenced the next generation of modernist practitioners.

Born in Ghent in 1861, Horta began his career as an architect in Paris before settling in Brussels in the 1880s. His breakthrough came with the Hôtel Tassel and he maintained starchitect status through the turn of the century. While he enjoyed a long and prolific professional arc that spanned many decades and included many public, institutional, and government projects, his legacy was secured with a series of four townhouses—Hôtel Tassel, Hôtel Solvay, Hôtel Van Eetvelde, and Maison-Atelier Horta—all designed and built in Brussels between 1892 and 1901 and recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites since 2000.

Aristocratic, avant-garde, and bespoke, Horta’s most celebrated townhouse designs anticipated the modern movement through dynamic open plan layouts enabled by cast iron technology—long before this approach made its way into the work of modernist pioneers like Le Corbusier. For his well heeled, cosmopolitan clients, Horta delivered homes unlike anything seen before, complete with original, handmade interior elements that elaborated on his overarching architectural program. Never editioned and sold on the market, Horta’s furniture, lighting, textiles, and tableware were site-specific to each of his architectural projects, designed to contribute to the architectural gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art. This kind of all-encompassing harmony between architecture and interiors was all the rage in fin de siècle design culture, also employed by Austrian architect Josef Hoffmann, French architect Hector Guimard, and Scottish architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh, among others.

Widely considered the first work of Art Nouveau architecture, Hôtel Tassel was the earliest of Horta’s townhouses and fully expressed his signature design grammar, thanks to his equally courageous patron, scientist and professor Emile Tassel, who gave Horta the freedom to realize his vision without constraint. Here, Horta first domesticated greenhouse architecture, borrowing the structural metal pillars usually found in public spaces to free the home from claustrophobic interior walls. “Discard the flowers and the leaves, and take the stem,” Horta once said of the revolutionary pillar form he favored.

Hôtel Van Eetvelde, completed in 1899, is the most majestic of Horta’s townhouses and features a striking winter garden theme. It was commissioned by Edmond van Eetvelde, administrator of newly formed Congo Free State (1885-1908), and was utilized for government receptions. Soon after its completion, Art Nouveau became the official style of the colonized territory in Central Africa, which was privately owned by the Belgian monarch, King Leopold II.

The flourishing of Art Nouveau in this colonial context, it must be noted, is enmeshed in a dark history. Leopold II’s colonialist enterprise in what is known today as the Democratic Republic of the Congo was marked by inconceivable savagery. The Belgian king oversaw the intensive extraction of natural resources in the Congo, including rubber, wood, ivory, and minerals, while enacting brutal forced-labor policies under threat of death, rape, and mutilation. Millions of Congolese people suffered and died.

Despite the Belgian king’s repeated assurances that his intentions in Africa were humanitarian in nature, by the turn 20th century, the barbarity of Belgian colonialism had become a massive international scandal. Starting in 1890, a growing number of high-profile voices ignited an international outcry against the human rights abuses in the Congo Free State, including Joseph Conrad, Arthur Conan Doyle, E. D. Morel, William Henry Sheppard, Mark Twain, and George Washington Williams. Following nearly two decades of increasing international pressure, Leopold II ceded his claim on the region in 1908, but the effects of his genocidal regime continue to be felt to this day.

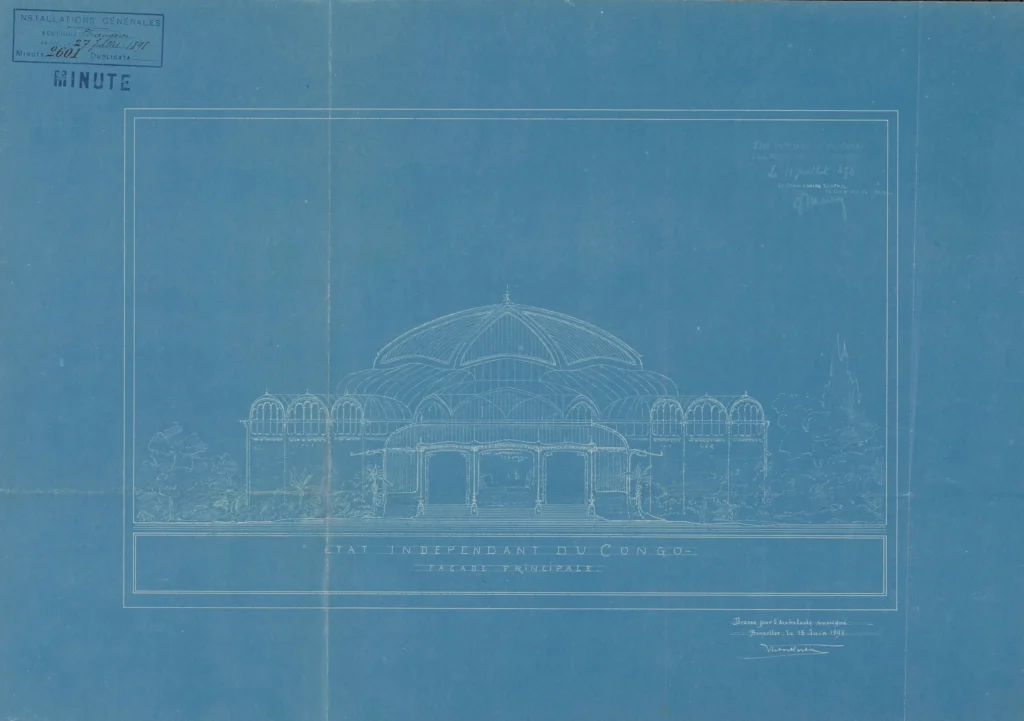

In 1897, Horta accepted another commission from Van Eetvelde: celebrating and promoting the Congo Free State on the international stage through a pavilion for the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. In response to the brief, Horta designed a massive glass and steel modular structure that he intended to relocate to the Congo after the Paris fair closed. As Camille Paget of the Horta Museum explains in an edifying video series produced by BOZAR, “rapidly spreading news of atrocities in the Congo derailed the project, and the pavilion was never built.”

My fascinating and complex discussion with Strauven concluded on the topic of Horta’s Maison du Peuple (House of the People) in Brussels, completed in 1899. Commissioned by the Workers’ Party of Belgium, this four-story, multi-purpose public building adds an underappreciated layer to the architect’s legacy, demonstrating that Horta was in fact dedicated to socialist causes, even as he regularly produced luxurious homes for the wealthy. Comprising a café, library, shops, offices, and meeting spaces, Horta’s Maison du Peuple took a highly functionalist approach, maximizing usable space and natural light and minimizing extraneous ornamentation. When the building was demolished in 1965 to make way for a commercial office tower, local and international protests erupted and led to the foundation of the architectural preservation movement in Belgium.

As Art Nouveau fell out of favor in the first decade of the 20th century, Horta’s stature declined as well. His design for the Belgian Pavilion at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris radically departed from the Art Nouveau grammar he helped define, resulting in a rather generic, rectilinear structure that drew little attention. Amid the onset of WWI, he relocated to London and then to the US, where he accepted an appointment as Professor of Architecture at George Washington University in Washington, DC. Upon his return to Belgium in 1919, he sold his house and studio and continued to work without much fanfare.

In the 1920s, alongside eight other European architects of the same generation, Horta juried the competition to design the UN Palace of Nations in Geneva. When the jury selected a historicist, neoclassical design, many in the international architectural community relegated Horta and his Art Nouveau-era contemporaries to the dustbin of 19th-century history. During WWII, he burned his design archive, and in 1947 he died, virtually forgotten. Thankfully his oeuvre was rediscovered in the wake of the Art Nouveau revival that swept Europe and the US in the 1960s and 70s.

From my own travels, I know that Horta’s architectural genius can only be fully understood when it is experienced in person. Even the best photography cannot capture the capaciousness of his volumes and the transformative originality of his forms. The Maison-Atelier Horta, for example, now a public museum, is only six or seven meters wide. And yet, once you step inside, the space feels endless, overflowing with light and air from the glass roof above. One cannot help but feel wonder, as if face-to-face with an enigma.

This article was published today in Forum Magazine by Design Miami.

Thank you for your excellent article. It was the perfect read as I ease into celebrating my birthday today.