Photo © Robert Kaplan Collection

This season’s Collecting Design program opened with a conversation on French design of the 1980s, a brand-new area of collecting that has yet to establish supporting connoisseurship and scholarship. Now we turn our attention to American Arts and Crafts, an area of collecting that falls on the opposite end of the market spectrum. The first expression of the modern design created in the early years of the 20th century, this body of handcrafted, pared down, and rectilinear furniture and decorative arts has been building a dedicated collectorship since the 1970s, particularly in the wake of Princeton University Art Museum’s groundbreaking 1972 exhibition The Arts and Crafts Movement in America, 1876–1916.

By the 1980s, objects from the American Arts and Crafts Movement were in high demand on the secondary market, widely seen in the high-profile homes of collectors and celebrities, notably Steven Spielberg and Barbara Streisand. Later, Steve Jobs famously proclaimed his love for the simple yet meticulous sensibility and perfect proportions of American Arts and Crafts design, filling his own home with these objects after living in an empty home for decades. Today, the market is well established, and avid collectors can reference extensive scholarship and a rich history of major museum collections and exhibitions to understand the standards of valuation around condition, provenance, and quality. The trajectory and current state of American Arts and Crafts connoisseurship was the focus of my recent talk with Robert Kaplan, one of the world’s foremost experts in this enduring area of design collecting.

For the past 40 years, Kaplan, a former manager and coach of professional tennis players based in New Jersey, has been devoted to American Arts and Crafts, first as a collector and then as a dealer and researcher. Regularly traveling across the US, from Upstate New York and New Jersey to the Midwest and West Coast, where important Arts and Crafts houses were built in the early 20th century, he has discovered some of the best examples of furniture, lighting, ceramics, textiles, and architectural elements that the movement produced. Because Arts and Crafts proponents favored a total-work-of-art approach, many of these pieces were bespoke to the homes for which they were made. I was amazed to learn from Kaplan that despite the long history of this area of collectorship, fresh and rare museum-quality objects previously known only from photographs can still be found at small auction houses and country fairs.

Kaplan’s reputation for expertise is well earned. He knows each piece made for the early homes of Frank Lloyd Wright, for the houses created and inspired by Gustav Stickley, and for the landmark bungalows built in Southern California by Greene and Greene. Kaplan knows them all, including their location, provenance, and exhibition, acquisition, and auction history. It’s no wonder that he is regularly invited to consult for institutions, auction houses, and private collectors. Recognized as the preeminent source for stellar works not only by Wright, Stickly, Greene and Greene, but also by Dirk Van Erp and Charles Rohlfs, along with pottery produced by Grueby, Marblehead, Ohr, and Teco, among others.

In our conversation, Kaplan explained that the Arts and Crafts Movement flourished in the US as part of a larger mission to rescue the American home from what its proponents perceived to be the “decadent” values of the Victorian era. Focused on social reform more than mere aesthetics, it emerged in England in the later years of the 19th century, amid the rapid changes brought on by the Industrial Revolution, and reached its pinnacle between 1890 and 1910, propelled by the writings and lectures of John Ruskin and William Morris. “Simplicity of life, even the barest, is not a misery, but the very foundation of refinement,” Morris once said.

Both fathers of the Arts and Crafts Movement and their followers were passionate about preserving the “soul” of Britain through a return to the handmade, a refinement of taste, and a reconnection with the natural world. The Industrial Revolution, in their view, had not delivered improvements to the quality of life for many Britons, but rather led to the proliferation of pollution, low quality products, and terrifying working conditions in factories. An alternative vision coalesced around a belief that England was better, healthier, and more “itself”during the Middle Ages, when Britons’ everyday life was defined by the labor and products of handcraft. The revival of artisanal production was embraced as a tool for social and moral improvement as well as for elevating the working conditions of the makers. This reformist thinking soon spread beyond the British Isles and became a global phenomenon. The American Arts and Crafts Movement took root in hundreds of organizations, including the establishment of a number of utopian artist colonies and design schools that emphasized hands-on training and production techniques—similar ideas that fed the foundation of the Bauhaus in Germany.

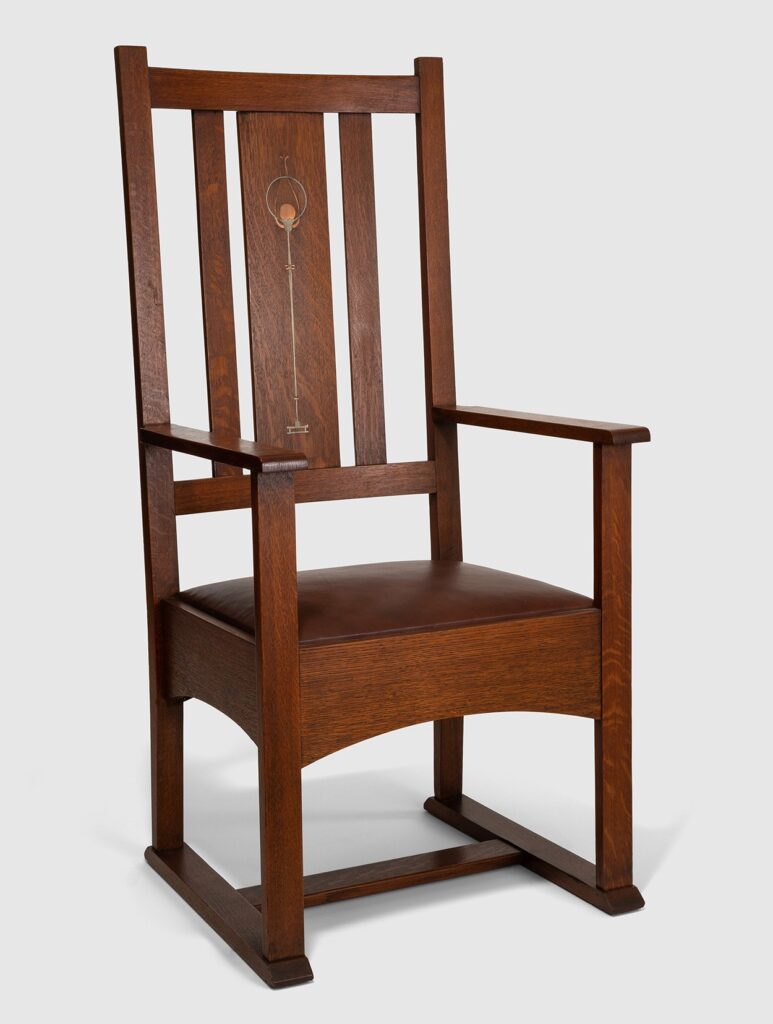

Kaplan spent a good deal of time speaking about Gustav Stickley (1858-1942), the New York-based furniture designer and merchant whose oak furniture, lighting, and metalwork accessories are a staple of major American Arts and Crafts private and public collections. Originally planned as a boarding school, his former home, Craftsman Farms in Morris Plains, New Jersey, was constructed from chestnut and stone in the style of local log cabins following principles defined by the heroes of the British Movement: Charles Robert Ashbee, C.F.A. Voysey, and Mackay Hugh Baillie Scott. Even in his own time, Stickley was considered a design star, among the most ambitious, successful, and influential of all American Arts and Crafts figures. The publication he founded, The Craftsman Magazine, served as the platform of the movement and its ideals while also promoting Stickley’s own production.

Stickley’s work, according to Kaplan, achieved the highest quality of proportion, scale, and craftsmanship. Between 1901 and 1904 in particular, Kaplan told us, Stickley produced his greatest work—elegantly simple furniture, lighting, and objets d’art often embellished with hammered metal surfaces. Stickley’s works from those early years are the most highly sought-after by museum curators and serious collectors and fetch six figures. Which is something of an irony given that Stickley endeavored to make his work accessible and “democratic.”

Born in Wisconsin, Stickley launched his career manufacturing furniture in the popular Victorian styles of the day, first through a company founded with his brothers in Michigan and later through his company Stickley & Simonds in New York. His vision changed in 1900, during a visit to England, where he discovered and fell in love with the progressive ideology of the Arts and Crafts Movement. He returned home determined to inject his own production with handcraft processes and the aesthetic principles of simplicity and honesty. That same year, Stickley unveiled his “New Furniture” at the annual trade show in Grand Rapids, marking the beginning of a new experimental direction. One exceptional example that Kaplan shared was the Damasus Plant Stand from 1901, which features features a green ceramic tile crafted by Boston-based pottery company Grueby.

What makes Stickley’s furniture great? According to Kaplan, it is his ability to fully capture the ideal of the movement: simplicity of form, honesty in construction, and quality of craftsmanship, especially in his structures using mortise and tenon joints, quarter-sawn oak, and other natural materials like leather and rush. But ultimately, Stickley’s greatness lies in his gift for scale and proportion. These characteristics are captured in a copper wall plaque that Kaplan showed us, which was produced in 1905, when Stickley first launched his metal workshop. It’s one of Kaplan’s favorites from his collection and was highlighted in the 1988 publication Treasures of the American Arts and Crafts Movement, authored by Beth Cathers and Tod M. Volpe.

Stickley did not have the courage and vision to change the direction of his work again when the craft message fell out of favor again, and so in 1915, he filed for bankruptcy and ceased publications of his magazine. His work remained obscured by history until it was rediscovered in the 1970s.

Frank Lloyd Wright was completely different in this respect; the American architect was able to evolve over and over again and to tailor his philosophy to the changing zeitgeist in every phase of his long seven-decade-long career. The furniture that Wright created during his Prairie School years is classified as Art and Crafts, because in the late 19th century, as he was leaving his draftsman position in the office of Louis Sullivan, he began to develop his own language inspired by the movement’s broader values. In fact, he summarized these principles in his 1908 essay collection In the Cause of Architecture. And the furniture he designed for the interiors of his architecture in this period is the rarest of the rare, collected by the most esteemed museums and private foundations.

As we discussed the value of Wright’s pieces today, Kaplan mentioned two pairs of high-back chairs by Wright sold at Christie’s New York in 2019. The chairs were produced circa 1902 for the Ward W. Willits House in Highland Park, Illinois—one of the finest examples of Wright’s Prairie Style architecture—part of an original suite of 11 dining chairs featuring geometrical frames in stained oak. Seven of these were designed with highly prized, very high backs and can now be found in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Victoria and Albert, St. Louis Museum of Art, High Museum of Art, and LACMA. The four chairs sold by Christie’s retained their original finish, had never been restored, and were offered publicly for the first time since they were made, but fetched a somewhat lesser value. Even so, the Christie’s chairs were the highlight of that auction season and were acquired by the Museum of the American Arts and Crafts Movement, which opened in St. Petersburg, Florida, in 2021.

As we learned from Kaplan, the A-list stars of American Arts and Crafts Movement have not changed over the years, and the best examples continue to earn high sales prices in public auctions and in private sales—the very definition of a well established collectible design market.

This article was published today in Forum Magazine; all photographa courtesy Robert Kaplan.

Photo © Robert Kaplan Collection