The names Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, and Dagobert Peche have long been synonymous with the triumph of early modernism. They were the leading figures of the Wiener Werkstätte (WW), a decorating firm established in Vienna in 1903. Their work was so innovative, influential, and spectacular that they were acknowledged by the very earliest writers of the history of modern design. But who were the others?—those artists, craftsmen, and designers who supported them, who crafted their designs, who were the active force behind these giants?

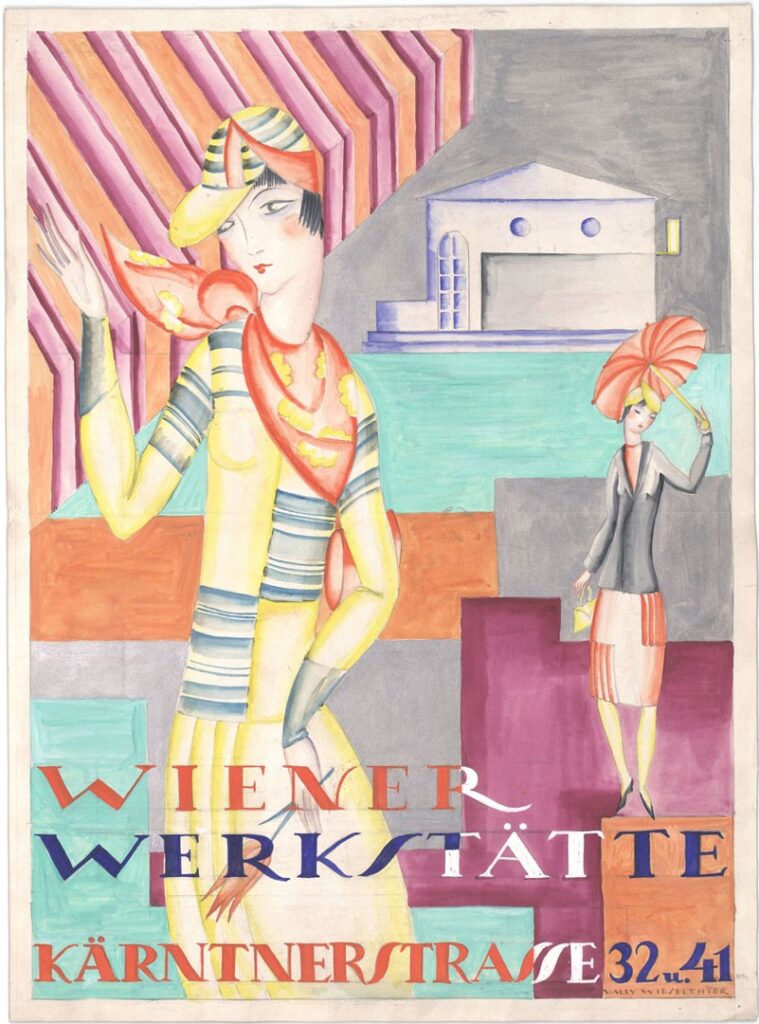

No fewer than 180 of them were women, we learn in a new exhibition at the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) in Vienna, ‘Women Artists of the Wiener Werkstatte.’ Accompanied by a scholarly publication (in German and English), it reveals and celebrates the role of female artists in the legendary WW.

The profession of female decorative artists has its roots in the 19th century. While at the beginning of the century women were excluded from many areas of economic life and were denied access to academic education and art schools, this had begun to change by the 1860s. No longer merely fulfilling roles as mothers and housewives, the female artists of that period were finally allowed admission to the first art schools for women, as there was an urgent need for an artistically trained workforce. In Austria, the School of Arts and Crafts was the first state vocational school to admit women, beginning in 1868. Hoffmann and Moser, founders of the WW, were both professors at the prestigious school, and naturally hired female graduates.

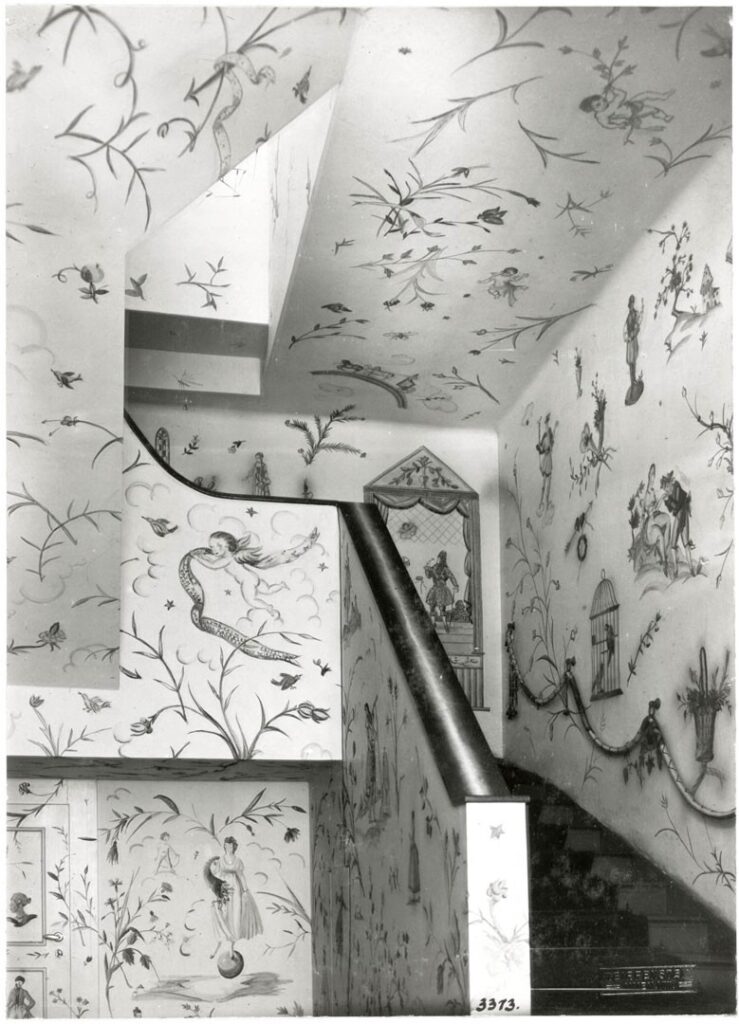

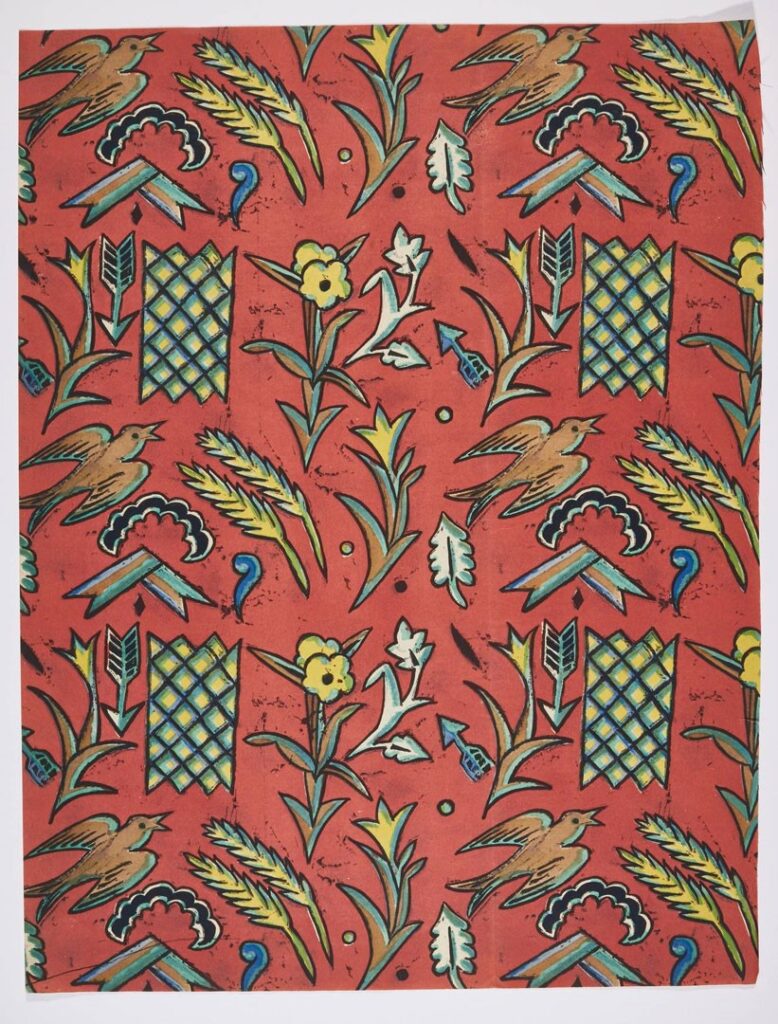

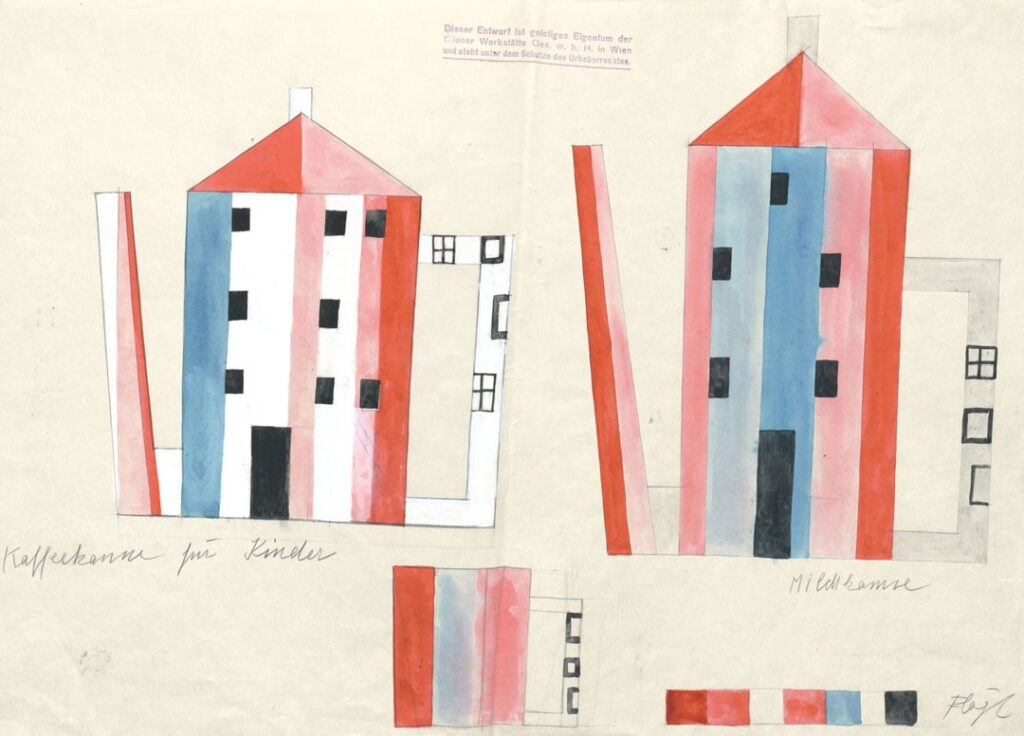

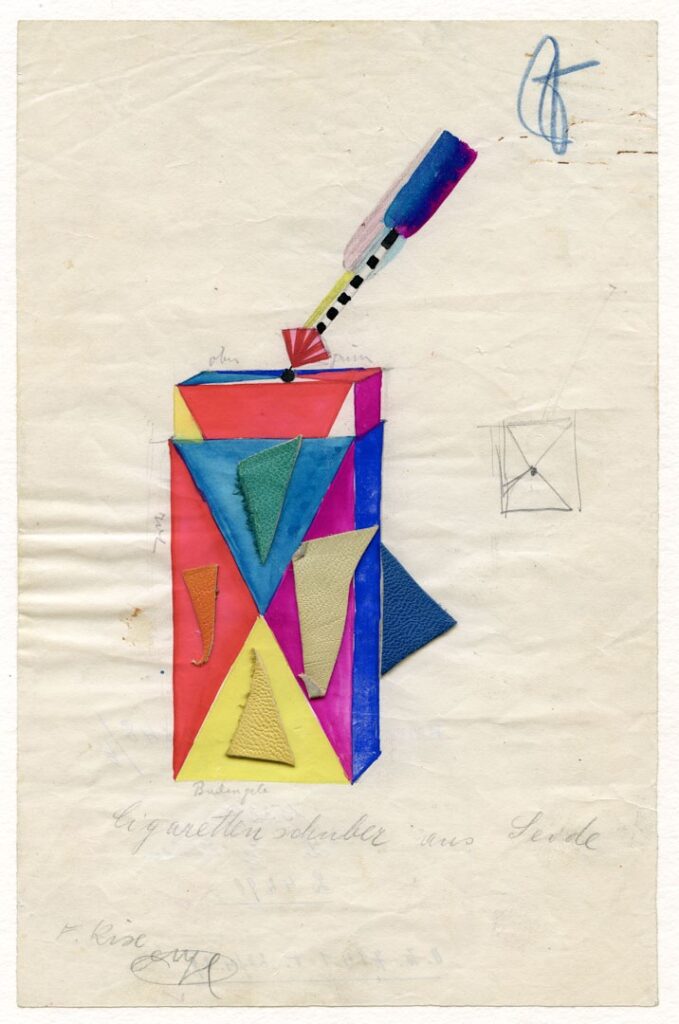

Thus, from the outset, women artists were involved in the production of the WW, and their number grew constantly until the company’s liquidation in 1932. They were particularly involved in the workshops of textile and fashion, ceramic and glass, and metal and enamel, taking leading roles in defining the ‘look’ of the WW, replete with extraordinary fabric patterns, expressive ceramic ware, stylish home accessories, and exceptional murals for interiors. These flats, restaurants or exhibition spaces, and progressive fashion and jewelry, were all created by 80 female artists, approximately half of whom are represented in the exhibition. Among them, the most well-known are Mathilde Flögl, Maria Likarz, Felice Rix, and Vally Wieselthier. Although highly recognized in their time, the women artists were mostly forgotten after the demise of the WW.

The catalog addresses a wide variety of topics related to the life and work of the female artists at the Wiener-Werkstätte; the place of the School of Arts and Crafts in cementing their careers; their roles in creating toys, postcards, fashion, and ceramics; and the final chapter, revealing the relationship between the Bauhaus and the WW. The two institutions differed, as the Bauahus designed simple products, and WW sought to create products of luxury. However, one commonality was the fear that admitting women might damage their reputations, as women were deemed less capable of creativity.

The catalog and exhibition give a face to the 180 women who helped make the WW a success and to raise awareness for an oeuvre that was involved in constituting the unique position of the Wiener Werkstätte. It is one of several publications and exhibitions occupied with female designers, and which I will cover here in the next few months. All images courtesy MAK.

I asked Elisabeth Schmuttermeier, the exhibition curator:

Did the fact that so many female artists were employed by the WW a result of the progressive view that its founders inherited from the Pre Raphaelites/Arts and Crafts Movement?

The Pre Raphaelites and the Arts and Crafts Movement did not result in the employment of women. It was the need of the art industry for an artistically trained workforce and the growing number of unmoyended middle-class women without any prospect of gainful employment. Several schools for handicraft accepted young women as pupils. Most important was the School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna who was the first state vacation school to admit women. The majority of the women artists of the Wiener Werkstätte were trained as pupils of Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser or Carl Otto Czescka in that school. The teacher engaged the female pupils to work in the Wiener Werkstätte because they were informed and convinced about their artistic ability. The women artist benefited from this, not least when the Artists Workshop was launched as a site experiment in 1916. From this moment on a particularly large number of women – in part due to the war – defined the WW’s creative output, yet even in the cooperative’s early days there is evidence of several women working there.

Have you found if your research whether an employment of women artists existed in contemporary endeavors (such as the Colony in Darmstadt or Art Nouveau productions in Nancy)?

We did research about the women artists employed in the Bauhaus. The peak of the Colony in Darmstadt or in Nancy is earlier than in Vienna.

Can you trace a ‘feminine’ mode in the work done by female artists in comparison to the work done by male artists/designers?

We did not trace a ‘feminine’ mode in the work done by female artists. Dagobert Peche, another famous male designer of the WW, created very similar designs in his oeuvre as the designs of the women artists. It was the special gift of the women of the WW for graphic or textile design etc. that authorized them to do those designs in the WW.

I am curating a show on female designers of the mid-century, and I have found that while they were highly productive in creating ceramics, jewelry, fashion, and fiber art, rarely did women design cutting-edge furniture and lighting. Was this the case at the WW too?

For the association “Wiener Kunst im Hause” a forerunner of the WW, even the female members designed furniture and lighting. (My article in the catalogue on page 36…) In the WW the women artist did rarely design for those species. We could not get out why?

During its 29 years, was any shift or change in the role and in the employment of female artists at the WW?

At the beginning the female pupils of the School of Arts and Crafts were engaged by the WW for the execution of objects like Therese Trehan for painting of Easter Eggs – the design of the painting was by Koloman Moser. Later-on the women have been working in both positions as designers and executors for graphic design, ceramics, jewelry.