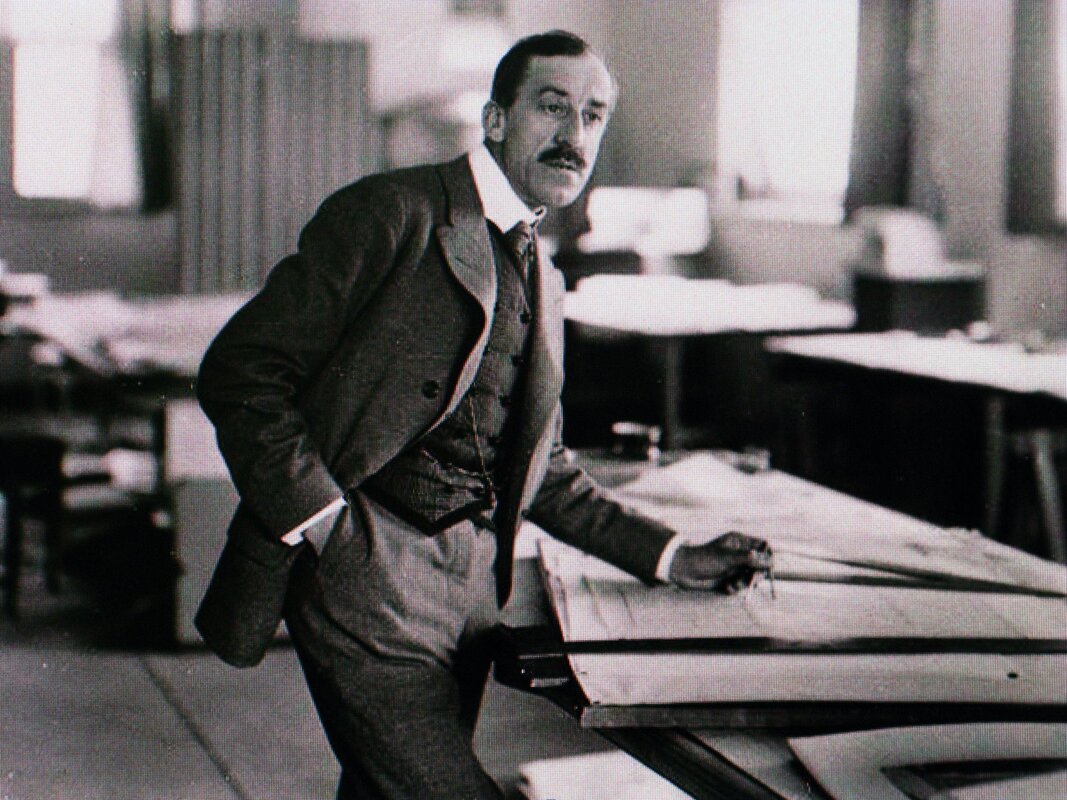

He was no less successful than Mies van der Rohe; no less modernist than Le Corbusier; no less political than Walter Gropius; and no less innovative than Erich Mendelsohn. He was as reformed, prolific, and legendary as them all, yet, the name of Belgium designer Henry van de Velde (1863-1957), who gave up painting at 30 to forge a long lasting and iconic career in design has remained somewhat obscured. Perhaps because he did not create monuments which made history and many of his important projects were not survived beyond a series of black-and-white photographs; perhaps he did not invest in forging a future legacy as did his contemporary Louis Comfort Tiffany; or perhaps there was nothing heroic about his biography. Henry Van de Velde, however, was present at all of the key intersections of his time, from Art Nouveau, through Arts and Crafts, to Expressionism, to Modernism, creating headlines one after the other.

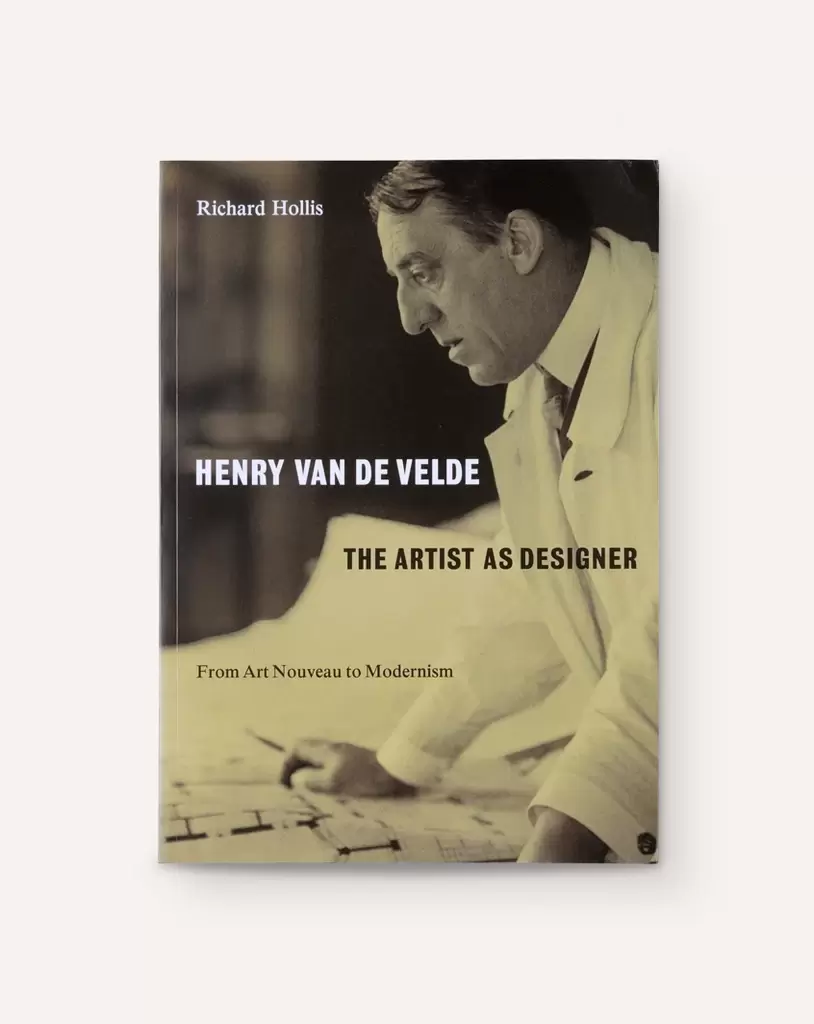

Now, with a new monograph ‘Henry van de Velde, The Artist as Designer, from Art Nouveau to Modernism,‘ by Richard Hollis (published by Publisher Occasional Papers) his diversified career is fully explored, exposed, and celebrated. The discovery of the long-forgotten enigma, who entered the historiography of design through a fraction of what he accomplished won’t rescue his legacy, because the taste of today is unlikely to embrace van de Velde’s work, and to recognize his greatness.

In this publication, you will find the enormous scope of van de Velde’s oeuvre, the stories behind the scenes, his struggles, conflicts, and successes, demonstrating a rare ability to change and adapt according to the zeitgeist. He worked in Brussels, Paris, Berlin, and Weimar, and was always at the forefront of innovation. He knew how to craft sensational interiors, how to created revolutionary furniture, stylish tableware, and he built the Grand Ducal Saxon School of Applied Art in Weimar, where he taught before it was incorporated into the more famous Bauhaus. Van de Velde’s own home, Bloemerwef, which he completed in 1896 in Uccle, Belgium was one of the most avant-garde houses of its time, where he created the building, interiors, furniture, tabletop, and even a variety of dresses for his wife, each to complement another room, a total integrated work of art, the ultimate gesamtkunstwerk.

I wish the book had more critical analysis of Van de Velde’s work. One of the highlights of his career, the theater he built at the 1914 Werkbund Exposition, lead the way to German Expressionism and was controversial and politically charged. I wish, such key projects would get an extra attention. Yet, Henry van de Velde, the Artist as Designer is filled with invaluable information, a mandatory book in any library with a focus on design and architecture.

Now, with a new monograph ‘Henry van de Velde, The Artist as Designer, from Art Nouveau to Modernism,‘ by Richard Hollis (published by Publisher Occasional Papers) his diversified career is fully explored, exposed, and celebrated. The discovery of the long-forgotten enigma, who entered the historiography of design through a fraction of what he accomplished won’t rescue his legacy, because the taste of today is unlikely to embrace van de Velde’s work, and to recognize his greatness.

In this publication, you will find the enormous scope of van de Velde’s oeuvre, the stories behind the scenes, his struggles, conflicts, and successes, demonstrating a rare ability to change and adapt according to the zeitgeist. He worked in Brussels, Paris, Berlin, and Weimar, and was always at the forefront of innovation. He knew how to craft sensational interiors, how to created revolutionary furniture, stylish tableware, and he built the Grand Ducal Saxon School of Applied Art in Weimar, where he taught before it was incorporated into the more famous Bauhaus. Van de Velde’s own home, Bloemerwef, which he completed in 1896 in Uccle, Belgium was one of the most avant-garde houses of its time, where he created the building, interiors, furniture, tabletop, and even a variety of dresses for his wife, each to complement another room, a total integrated work of art, the ultimate gesamtkunstwerk.

I wish the book had more critical analysis of Van de Velde’s work. One of the highlights of his career, the theater he built at the 1914 Werkbund Exposition, lead the way to German Expressionism and was controversial and politically charged. I wish, such key projects would get an extra attention. Yet, Henry van de Velde, the Artist as Designer is filled with invaluable information, a mandatory book in any library with a focus on design and architecture.

Above: Henry van de Velde, porcelain plate for Missen, 1904, courtesy Wright.